Whilst the main events of the story did indeed take place, despite being a fairly enjoyable read I think it comes closer to an adventure from the Enid Blyton stable than being a "true and detailed account" of what actually happened - some aspects seem suspiciously detailed considering they were written about so much later.

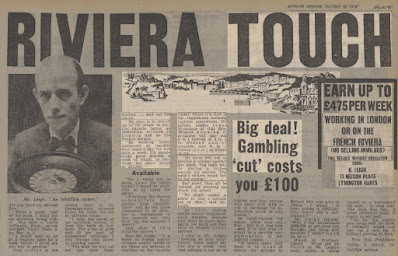

New Milton Advertiser - Saturday 24 January 1976Not a good weekend for Norman LeighLast weekend was not a very good one for Mr. Norman Horace William Leigh (47), of 11, Nelson Place, Lymington.The "Sunday Mirror" published an investigation into his activities, and on Monday he appeared at Lymington Magistrates' Court where he was fined £10 for being drunk and disorderly the day before in the High Street and Captain's Row,The "Sunday Mirror" article dealt with an investigation into Mr. Leigh's past, and his offer to the public suggesting they could earn large sums if they bought his infallible gambling system. His posters read: "Earn up to £475 a week working in London or on the French Riviera (no selling involved). Full details without obligation".For only £100 plus 25 per cent of the winnings, Mr. Leigh will sell the secret of his roulette system. He said his plan was to recruit 100 people to play the roulette tables as individuals at clubs in London and on the French Riviera. "By working inconspicuously at roulette four hours a day, for five days a week, 100 people could gross £50.000 a week of which, by contract, my share would be £12,500." he told Lawrence Turner, who did the investigation.In case anyone might be anxious to try their luck, the "Sunday Mirror" also revealed that Mr. Leigh has a record as a confidence trickster, and was sentenced to five years in jail in 1970 for what the prosecution called "a heartless fraud on people seeking homes." Mr. Leigh claims he was framed.

Never having succeeded, he convinced himself of the validity of a theory published in 1923 by the Hon.S.R.Beresford, third son of the third Baron Decies, that the reason people lost so much playing roulette was less about the impact of the house edge and more about the consequence of increasing bets when losing and chasing losses.

Following on from this he adopted the Honourable Mr B's suggested "system", which takes the already known Labouchere negative progression system (one where you bet more when losing to recover losses), and simply reverses the staking plan to arrive at the Reverse Labouchere - bets would be progressively increased as successive wins occurred, but remained constant when they didn't.

The premise of this unbeatable system seems to be based on the chance that streaks of continuous winning results will occur often enough, and continue for long enough to reach the table limit, to generate sufficient winnings to offset the losses resulting from the zero being spun and the house edge biting.

Some have suggested that perhaps mathematics may not have been the author's strong point, although I'm not so sure. In his story he contributed none of his own capital to the enterprise and all of his team were required to pay all of their own travel and accommodation expenses, and provide a minimum amount of £250 stake money (the equivalent of £4,200 today) in order to apply his system in France - he carried no financial risk, apart from his own travel and accommodation expenses, and made his money by taking 10% of any winnings.

I suppose a question is could the Reverse Labouchere be applied today, on the prospect of just getting lucky. Sure, and you might just be so. But as casinos nowadays have a five or ten times table minimum bet requirement on evens-payout options, and maximums of 500 or 1000 times table minimum, the scope for recouping sustained losses from progressing to the table limit is fairly limited over what it may have been in the past. You could reduce the exposure by betting 6 lines (6 lots of 6 numbers, so all of them bar the zero) at the table minimum with a co-player, which would mean betting 6 units per spin rather than 20 but achieving the same coverage and providing some el-cheapo entertainment into the bargain. It might be fun, but don't be under any illusions that the longer term prospects for this system lead South. Accurate and comprehensive record keeping will expose it's fallibility.

After reading the book, I did wonder what became of Norman Leigh? Half an hour searching the web provided the answer; I came across some postings from someone who knew and had played roulette with him together with two entries on the Amazon review page for Thirteen against the Bank from his niece and his ex-wife, Pauline.

Thirteen against the Bank was reprinted in 2006 and remains available from all major book retailers.

November 2014

Postscript

Shortly after I finished reading Thirteen against the Bank I wrote to Pauline, Norman Leigh's ex-wife, and she kindly agreed to meet me and answer some questions . . .

Q. Was the team really made up of an Etonian, a publican, an ex-copper, a glamorous mum, an elderly widow etc? Can you recall the backgrounds of the team members you met?

A. I think the characters portrayed in the book are a fairly accurate reflection of the team's mix. The Etonian, named as "Blake" in the book, who acted as Norman's second, was actually a stockbroker. All of the characters' names have been changed of course, and I think it would be indiscreet of me to name them.

Q. Was the team's barring from the Casino Municipale in Nice carried out in the respectful manner described in the book, or was it simply a case of them being turned away at the door one day with no reason being given? Are you able to elaborate?

A. I don't know as I didn't join the team until after they had been barred from playing at the Casino Municipale in Nice.

Q. At what point did the French police become involved (if at all) and to what extent?

A. Again, I don't know. The team certainly wasn't ejected from the Country, as after I joined them we stayed in France for a further three weeks and returned home voluntarily (and broke).

Q. After the team's members were barred, did you all travel to any other casinos in France to try your luck?

Yes. By the time I joined the team they were already playing at the Casino du Palais de la Mediterranee, which is also in Nice.

Q. Do you know how much money was actually won or lost on the trip - for Norman and the individual team members?

A. No. I became aware that things weren't going too well when the letters Norman had been sending home, that contained French banknotes, dried up and the amount of money we had to pay for our stay in France dwindled; we went from enjoying three meals a day to having just one. Eventually, after three weeks, a meeting of the team was called to decide whether to continue or not. Norman was all for carrying on, but the majority voted not to and to return home. I recall that towards the end of the discussions "Blake" turned to Norman and said, "Mr Leigh, you are a dreamer and your wife is a realist!".

Norman and I travelled back to England, all the way through France, by train on third class rail tickets. Some members of the team, who were staying in better hotels and were not short of funds, opted to stay.

Q. Your father gets a mention in the book, and Norman describes him as "old school" when meeting him for the first time. What was his reaction to the plan to travel to France to break the bank at roulette?

A. If I recall rightly he was calm and uncommitted when I told him of the plan, and said something along the lines of "if that's what you want to do, good luck".

Q. After returning to the UK, were there any plans for the team to continue playing together in casinos in Britain?

A. No. I'm pretty sure that those members of the team who returned home had all lost money.

Q. Did you and/or Norman ever meet up with any of the team members after the return from France?

A. Just once. Norman and I met up with one couple for dinner, but that was the only time.

Q. Did Norman subsequently continue to play roulette and plan around "beating the wheel"?

A. I'm sure he did. He always had one scheme or another in hand, including selling "winning systems".

Q. In the book's foreword, Norman admits to having been convicted on a fraud charge in 1968 and of serving time as a result (although he doesn't state how long). Is this something that happened whilst you were still together? If so, would you be willing to share the details?

A. I'm afraid I can't recall the circumstances of the case or the charges. Around that time we had to give up our house in Twickenham. I'd foolishly allowed him to use my name on some HP agreements, and shortly after that he was convicted and accommodated by Her Majesty's Prison Service. I know he was sent to prison on more than one occasion and was made bankrupt.

Q. Are you able to provide any details of Norman's fortunes after your separation and divorce?

A. After we separated I returned to the Isle of Wight and Norman was convicted. Our divorce formalities took longer to conclude than they needed to as a result of Norman making difficulties from prison. After he was released, he did contact me and ask if I could help him out with some money, but I declined - during our marriage, all of my savings and a bequest from an Aunt were used up supporting his schemes.

Before we were married, Norman had worked as an Insurance Agent for a short time, but resigned due to a dispute over sales and withheld commissions, and I think that was the last time he ever had a real job. Norman did come and meet our son, Julian, and a vague contact ensued until the time of Norman's death - which Julian found out about through seeing a local press headline on a newsagent's billboard.

Norman's last address was a room at the Catisfield Hotel in Fareham, which to all intents and purposes was a DSS hostel. After his death I was contacted and asked if I would go there and clear out his effects, which I did. He didn't have much and was given a pauper's funeral.

Norman's estate is still managed by an agent, and the TV and film rights to his book are renewed by a production company every two years.

Many thanks to Pauline for indulging my curiosity.

Further reading: https://rss.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1740-9713.2018.01211.x

Based on our simulations, we conclude that the book Thirteen Against the Bank by Norman Leigh is a work of fiction – which is a shame as it is a very nice story – and that the system it describes cannot, and does not, consistently return a profit. Our future work will include simulating other betting systems, including those of the game of blackjack, so that the scientific archive, and the general public, have a point of reference for systems which claim to “break the bank”.