Sunday, 1 April 2001

Friday, 2 February 2001

Thirteen Against The Bank by Norman Leigh

Whilst the main events of the story did indeed take place, despite being a fairly enjoyable read I think it comes closer to an adventure from the Enid Blyton stable than being a "true and detailed account" of what actually happened - some aspects seem suspiciously detailed considering they were written about so much later.

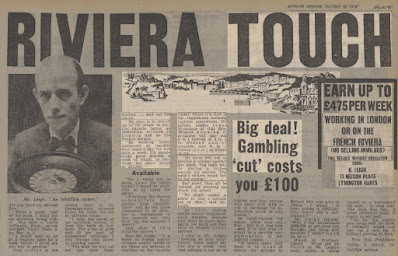

New Milton Advertiser - Saturday 24 January 1976Not a good weekend for Norman LeighLast weekend was not a very good one for Mr. Norman Horace William Leigh (47), of 11, Nelson Place, Lymington.The "Sunday Mirror" published an investigation into his activities, and on Monday he appeared at Lymington Magistrates' Court where he was fined £10 for being drunk and disorderly the day before in the High Street and Captain's Row,The "Sunday Mirror" article dealt with an investigation into Mr. Leigh's past, and his offer to the public suggesting they could earn large sums if they bought his infallible gambling system. His posters read: "Earn up to £475 a week working in London or on the French Riviera (no selling involved). Full details without obligation".For only £100 plus 25 per cent of the winnings, Mr. Leigh will sell the secret of his roulette system. He said his plan was to recruit 100 people to play the roulette tables as individuals at clubs in London and on the French Riviera. "By working inconspicuously at roulette four hours a day, for five days a week, 100 people could gross £50.000 a week of which, by contract, my share would be £12,500." he told Lawrence Turner, who did the investigation.In case anyone might be anxious to try their luck, the "Sunday Mirror" also revealed that Mr. Leigh has a record as a confidence trickster, and was sentenced to five years in jail in 1970 for what the prosecution called "a heartless fraud on people seeking homes." Mr. Leigh claims he was framed.

Never having succeeded, he convinced himself of the validity of a theory published in 1923 by the Hon.S.R.Beresford, third son of the third Baron Decies, that the reason people lost so much playing roulette was less about the impact of the house edge and more about the consequence of increasing bets when losing and chasing losses.

Following on from this he adopted the Honourable Mr B's suggested "system", which takes the already known Labouchere negative progression system (one where you bet more when losing to recover losses), and simply reverses the staking plan to arrive at the Reverse Labouchere - bets would be progressively increased as successive wins occurred, but remained constant when they didn't.

The premise of this unbeatable system seems to be based on the chance that streaks of continuous winning results will occur often enough, and continue for long enough to reach the table limit, to generate sufficient winnings to offset the losses resulting from the zero being spun and the house edge biting.

Some have suggested that perhaps mathematics may not have been the author's strong point, although I'm not so sure. In his story he contributed none of his own capital to the enterprise and all of his team were required to pay all of their own travel and accommodation expenses, and provide a minimum amount of £250 stake money (the equivalent of £4,200 today) in order to apply his system in France - he carried no financial risk, apart from his own travel and accommodation expenses, and made his money by taking 10% of any winnings.

I suppose a question is could the Reverse Labouchere be applied today, on the prospect of just getting lucky. Sure, and you might just be so. But as casinos nowadays have a five or ten times table minimum bet requirement on evens-payout options, and maximums of 500 or 1000 times table minimum, the scope for recouping sustained losses from progressing to the table limit is fairly limited over what it may have been in the past. You could reduce the exposure by betting 6 lines (6 lots of 6 numbers, so all of them bar the zero) at the table minimum with a co-player, which would mean betting 6 units per spin rather than 20 but achieving the same coverage and providing some el-cheapo entertainment into the bargain. It might be fun, but don't be under any illusions that the longer term prospects for this system lead South. Accurate and comprehensive record keeping will expose it's fallibility.

After reading the book, I did wonder what became of Norman Leigh? Half an hour searching the web provided the answer; I came across some postings from someone who knew and had played roulette with him together with two entries on the Amazon review page for Thirteen against the Bank from his niece and his ex-wife, Pauline.

Thirteen against the Bank was reprinted in 2006 and remains available from all major book retailers.

November 2014

Postscript

Shortly after I finished reading Thirteen against the Bank I wrote to Pauline, Norman Leigh's ex-wife, and she kindly agreed to meet me and answer some questions . . .

Q. Was the team really made up of an Etonian, a publican, an ex-copper, a glamorous mum, an elderly widow etc? Can you recall the backgrounds of the team members you met?

A. I think the characters portrayed in the book are a fairly accurate reflection of the team's mix. The Etonian, named as "Blake" in the book, who acted as Norman's second, was actually a stockbroker. All of the characters' names have been changed of course, and I think it would be indiscreet of me to name them.

Q. Was the team's barring from the Casino Municipale in Nice carried out in the respectful manner described in the book, or was it simply a case of them being turned away at the door one day with no reason being given? Are you able to elaborate?

A. I don't know as I didn't join the team until after they had been barred from playing at the Casino Municipale in Nice.

Q. At what point did the French police become involved (if at all) and to what extent?

A. Again, I don't know. The team certainly wasn't ejected from the Country, as after I joined them we stayed in France for a further three weeks and returned home voluntarily (and broke).

Q. After the team's members were barred, did you all travel to any other casinos in France to try your luck?

Yes. By the time I joined the team they were already playing at the Casino du Palais de la Mediterranee, which is also in Nice.

Q. Do you know how much money was actually won or lost on the trip - for Norman and the individual team members?

A. No. I became aware that things weren't going too well when the letters Norman had been sending home, that contained French banknotes, dried up and the amount of money we had to pay for our stay in France dwindled; we went from enjoying three meals a day to having just one. Eventually, after three weeks, a meeting of the team was called to decide whether to continue or not. Norman was all for carrying on, but the majority voted not to and to return home. I recall that towards the end of the discussions "Blake" turned to Norman and said, "Mr Leigh, you are a dreamer and your wife is a realist!".

Norman and I travelled back to England, all the way through France, by train on third class rail tickets. Some members of the team, who were staying in better hotels and were not short of funds, opted to stay.

Q. Your father gets a mention in the book, and Norman describes him as "old school" when meeting him for the first time. What was his reaction to the plan to travel to France to break the bank at roulette?

A. If I recall rightly he was calm and uncommitted when I told him of the plan, and said something along the lines of "if that's what you want to do, good luck".

Q. After returning to the UK, were there any plans for the team to continue playing together in casinos in Britain?

A. No. I'm pretty sure that those members of the team who returned home had all lost money.

Q. Did you and/or Norman ever meet up with any of the team members after the return from France?

A. Just once. Norman and I met up with one couple for dinner, but that was the only time.

Q. Did Norman subsequently continue to play roulette and plan around "beating the wheel"?

A. I'm sure he did. He always had one scheme or another in hand, including selling "winning systems".

Q. In the book's foreword, Norman admits to having been convicted on a fraud charge in 1968 and of serving time as a result (although he doesn't state how long). Is this something that happened whilst you were still together? If so, would you be willing to share the details?

A. I'm afraid I can't recall the circumstances of the case or the charges. Around that time we had to give up our house in Twickenham. I'd foolishly allowed him to use my name on some HP agreements, and shortly after that he was convicted and accommodated by Her Majesty's Prison Service. I know he was sent to prison on more than one occasion and was made bankrupt.

Q. Are you able to provide any details of Norman's fortunes after your separation and divorce?

A. After we separated I returned to the Isle of Wight and Norman was convicted. Our divorce formalities took longer to conclude than they needed to as a result of Norman making difficulties from prison. After he was released, he did contact me and ask if I could help him out with some money, but I declined - during our marriage, all of my savings and a bequest from an Aunt were used up supporting his schemes.

Before we were married, Norman had worked as an Insurance Agent for a short time, but resigned due to a dispute over sales and withheld commissions, and I think that was the last time he ever had a real job. Norman did come and meet our son, Julian, and a vague contact ensued until the time of Norman's death - which Julian found out about through seeing a local press headline on a newsagent's billboard.

Norman's last address was a room at the Catisfield Hotel in Fareham, which to all intents and purposes was a DSS hostel. After his death I was contacted and asked if I would go there and clear out his effects, which I did. He didn't have much and was given a pauper's funeral.

Norman's estate is still managed by an agent, and the TV and film rights to his book are renewed by a production company every two years.

Many thanks to Pauline for indulging my curiosity.

Further reading: https://rss.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1740-9713.2018.01211.x

Based on our simulations, we conclude that the book Thirteen Against the Bank by Norman Leigh is a work of fiction – which is a shame as it is a very nice story – and that the system it describes cannot, and does not, consistently return a profit. Our future work will include simulating other betting systems, including those of the game of blackjack, so that the scientific archive, and the general public, have a point of reference for systems which claim to “break the bank”.

Thursday, 1 February 2001

Ron Pollard

From the Daily Telegraph's Obituary pages, 5 July 2015:

Ron Pollard, who has died aged 89, changed the face of British betting by taking the bookmaking business beyond horse and greyhound racing into the more exotic arenas of beauty contests, politics, book prizes and the arrival of aliens from outer space.

Guided by his principle that “betting should be fun”, Pollard’s genius was to realise that many punters would cheerfully bet on outcomes far less likely than their being struck by lightning. “It was abundantly clear”, he once said, “that the public would gamble on absolutely anything. If it moved, if it was on TV, if it caused an argument in a pub, they wanted to bet on it.”

His aim was always for his firm, Ladbrokes, to be first with anything new, thus raising its profile and encouraging more punters to use it. Having introduced betting on cricket, golf, tennis, darts and snooker, in 1977 Pollard offered odds on the existence of the Loch Ness Monster; in the same year Ladbrokes started to take bets on the arrival of aliens on Earth, giving 500-1 to a group in California run by a woman who claimed to be a reincarnation of the Mona Lisa.

Pollard offered odds of 1,000-1 against Elvis Presley returning from the dead. Although he conceded that this was a “tasteless exercise”, Ladbrokes took so much business that it soon had a £2·5 million liability, and he had to cut the price to 100-1. The safest bet he ever laid was placed by a teenage girl: 5,000-1 against her taking tea with a reincarnated Elvis by the end of 1982.

Although these stunts were not always profitable – Ladbrokes had offered 100-1 against a man walking on the moon in the 1960s – he appreciated that they reaped for his firm “the most precious commodity of all: publicity”.

Pollard did not attribute his success entirely to his own acumen. He was a self-confessed spiritualist who believed that he was guided by a 15th-century bearded Chinaman in a white skull-cap. His interest in this field had been aroused in 1955 when, aged 29, he accompanied his mother-in-law to Kennards, a department store in Croydon, where she consulted a medium.

Although then a sceptic, Pollard also saw the medium, who caressed the young man’s comb before pronouncing: “Goodness gracious, I wish I was going to have your life. You are going to be in all the papers, everyone wants to know what you are saying, and you are going to Buckingham Palace [to] meet members of the Royal Family.” It was she who alerted him to the presence of his Chinaman. Twenty-four years lat er Pollard was honoured as “Spiritualist of the Year”.

His greatest coup came in 1963, when he introduced betting on politics with the “Tory Leadership Stakes”: “For two weeks I did not know if I was a bookmaker or a film star. The telephone did not stop ringing. I was constantly on television and radio. Everyone wanted a quote.” Sir Alec Douglas-Home (the eventual winner, who had initially ruled himself out of the contest) was installed at 16-1; Ladbrokes took £14,000 on the exercise, making a profit of only £1,400. But the company was now known across the world.

At the next general election, in 1964, Ladbrokes opened a book. The hotelier Maxwell Joseph bet £50,000 on a Labour victory, winning £32,272 when Harold Wilson emerged with a five-seat majority. Had the Tories won, the firm would have lost £1·5 million — money it did not have. Pollard was so concerned about this outcome that he resolved to commit suicide in the event of a Conservative victory.

The £640,000 that Ladbrokes took on that election was the record at the time for any single event (including the Derby or the Grand National). In the general election of 1966 the firm took £1.6 million.

Before long, Pollard was being entertained by MPs at the House of Commons. At the time of the Conservative Party’s leadership election of 1975 he was invited to lunch at White’s, where someone inquired what odds he was offering on Margaret Thatcher to win the Tory leadership. Pollard replied: “Fifty to one.” Pollard’s companion confided: “I would be very careful if I were you.” The odds were immediately slashed to 20-1.

Occasionally, Pollard’s political antennae (or his Chinaman) let him down, as in the general election of 1970, which the Conservatives unexpectedly won, costing Ladbrokes around £80,000. Some members of the board wanted Pollard sacked; but the chairman, Cyril Stein, remained loyal, telling his colleagues: “If he goes, I go.” The odds-maker survived.

Ronald James Joseph Pollard was born in London on June 6 1926. His paternal grandfather distributed relief money to the unemployed, and would visit pubs in Southwark disguised as a chimney sweep to see if any of his clients were spending their welfare on beer. Although Ron’s father was the accountant to a mineral water company, the family had little money and his mother worked from home as a glove machinist. At school in Peckham Ron failed to shine academically but enjoyed playing football and cricket. He left with no qualifications.

He got a job as an office boy in a building firm at Peckham, learning bookkeeping. On Saturdays he went greyhound racing at Catford. Then, in 1943, he became a ledger clerk with William Hill at the bookmaker’s office in Park Lane. At first he ran errands, such as paying a jockey who had obligingly finished second on a hot favourite at Goodwood. At this stage Hill’s was operating illegally by handling cash betting, which was then allowed only on the racecourse (transactions off-course had to be on a credit basis).

Although he was called up for the Army, Private Pollard was still at Westcliff-on-Sea on VE Day. He then served on the Gold Coast, where he was promoted to sergeant and won the Gold Coast ping-pong championship two years in succession.

He returned to Britain in 1947, and was demobbed the following year, returning to work for William Hill. He was made a course clerk, recording the bets taken by the Hill’s representative, and occasionally acting as the bookmaker at some of the smaller meetings; he was then appointed manager of the accounts department.

Pollard joined Ladbrokes as credit manager in 1962, the year the firm opened its first betting shops. “These were still the days of credit betting, and you had an account with Ladbrokes at their Burlington Street offices only if you were in Debrett,” he said. “If you were in trade, no matter how prosperous, you had no chance of an account with the firm that had a direct telephone link to Buckingham Palace for the regular royal bets that would be struck, sometimes daily.”

Before long he had been appointed general manager of Ladbrokes, and, in 1964, he was made a director of Town and Country Betting, the Ladbrokes holding company which was to become Ladbroke Racing. In the same year he became the firm’s PR director, remaining there until his retirement in 1989.

Among Pollard’s most famous stunts were his forays into the Miss World contest. These did not endear him to the organisers, Eric and Julia Morley. After Julia Morley accused him, apparently without irony, of “dragging [the contest] into the cattle market”, and banned him from the Miss World rehearsals in a television studio, Pollard disguised himself as a carpenter (complete with overalls, cloth cap and a tool kit) and spent a morning assessing the attributes of the candidates on whom he was to make a book.

On another occasion he assumed the character of a waiter, sporting a false grey moustache, to penetrate the dining room at the Dorchester where the finalists were attending a function. Pollard was extremely successful in predicting the outcomes of Miss World, and in 1982 personally won £5,000 when Miss Dominican Republic took the title. His guiding principle was: “The sexy ones never win.”

When it came to fixing odds for the Booker Prize, Pollard would read the first 60 or so pages of a novel; a similar number in the middle; and the final 60.

Pollard himself was not a habitual gambler (betting “only when I thought I knew something”) and did not have a high opinion of those who were: “The reason why people bet has nothing to do with money. They do it because they want to get one up on the other fellow and because they want to be right.”

He was an entertaining man and a fine raconteur who courted, and made many friends among, the press. A lifelong socialist, his greatest regret was that he never became an MP; he claimed to have been offered a seat by all three main parties.

In 1991 he published an autobiography, Odds & Sods: my life in the betting business.

Ron Pollard is survived by his wife, Pat, and three children.

Ron Pollard, born June 6 1926, died June 10 2015

Navinder Singh Sarao – The Hound of Hounslow

It took Navinder Singh Sarao a long time to accept that he might have been scammed out of $50 million. Stuck in London’s Wandsworth prison, wracked with anxiety and unable to sleep, the realization dawned on the man dubbed the “Flash Crash Trader” as slowly as spring turned to summer outside the barred window of his jail cell.

The trauma of the past few weeks had been difficult to process. On April 20, 2015, the slight, doe-eyed 36-year-old had dozed off peacefully in the same suburban bedroom he’d slept in since he was a boy. The next day he was arrested and taken to a police station, where he was charged with 22 counts of fraud and market manipulation carrying a maximum sentence of 380 years.

According to the U.S. government, the British day trader had made tens of millions of dollars using an illegal practice called spoofing, including, fatefully, on the morning of May 6, 2010, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell almost 1,000 points in minutes before bouncing back. The extent of Sarao’s culpability for the flash crash is fiercely contested, but the incident exposed the shaky foundations on which the hyper-fast, computer-dominated financial markets now rest.

Sarao’s bail was set at 5.05 million pounds ($6.3 million). It was a hefty sum, but according to the accounts of his company, Nav Sarao Futures Limited, he’d earned 30 million pounds in the previous five years. Newspaper reports, in which Sarao was dubbed “The Hound of Hounslow,” speculated that he’d be back with his family in the shabby West London borough by the weekend.

Where’s the money, Nav, his lawyers wanted to know. Sarao couldn’t make bail, they gradually learned, because the bulk of his wealth was tied up in investments and offshore trusts, each more complicated than the last. Days in Wandsworth prison, a Victorian-era fortress where Sarao was housed with sexual predators and violent offenders, turned into weeks.

After four months of dead ends, his legal team struck a deal with the authorities: If the U.S. Justice Department and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission agreed not to oppose a reduction in bail to 50,000 pounds, the firm would act as a bounty hunter, taking on responsibility for tracking down the missing millions on the condition that its fees be paid if it did.

They were going down a rabbit hole. A review of Sarao’s investments from 2005 to the present day, based on dozens of interviews and thousands of pages of documents, reveals another twist in an already remarkable story.

Sarao declined to comment for this article. His lawyer, Roger Burlingame of Kobre & Kim in London, told a U.S. judge in November that all of the defendant’s assets “have been stolen.” Sarao invested in ventures from which he, the law firm and the CFTC had been unable to recover the funds, Burlingame said. “Basically, he has some extraordinary abilities with respect to pattern recognition and certain sorts of mathematical abilities, but he has some fairly severe social limitations.”

Sarao’s trading career started inauspiciously in 2002 at Futex, a fledgling outfit in an unglamorous office an hour from the City of London that housed wannabe traders in exchange for as much as 50 percent of their profit. In a roomful of recent college graduates and drifters, Sarao stood out from the pack.

“Nav was always going to be the kind of person that would be legendary in some way,” Futex Chairman Paolo Rossi said in an interview with Bloomberg TV after Sarao’s arrest. He had “the potential to be remembered as one of the world’s greatest traders.”

It wasn’t until Sarao left Futex in 2008 and struck out on his own that he started to make serious money. Public filings show his assets popped to 14.9 million pounds from 461,000 pounds in the 12 months ending in June 2009, long before he enlisted a programmer to build a system that authorities say was designed to cheat the market.

Former colleagues talk about Sarao’s frugality—his scruffy clothes, his reluctance to spend money on cars and watches, his abstemious eating habits. He learned early at Futex that withdrawing cash ate into his bankroll and reduced the size of trades he could place.

That near-obsessive drive to hold on to as much of his wealth as possible can also be seen in the way he conducted his business affairs. Looking to minimize his tax bill, he was introduced by his accountant to John Dupont, a director at the London arm of an Isle of Man-based financial advisory firm called Montpelier Tax Consultants.

Dupont, then in his mid-30s, was a high-energy salesman whose accent veered from upper class gent to Guy Ritchie cockney depending on who he was speaking with, a former employee recalls. Operating from an office on Cockspur Street in London’s West End, members of his team cold-called contractors, day traders and bankers and tried to enlist them in a range of plans to minimize their tax bills, documents seen by Bloomberg show.

The aim was to identify loopholes before they were closed. One former Montpelier employee said he coaxed wavering customers to sign up by promising to pay their legal bills in the event of a clampdown by Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs. Everyone at the firm thought he was Alec Baldwin in “Glengarry Glen Ross,” the person said.

Self-employed traders were particularly good prospects because they were predisposed to high levels of risk. And Sarao, an absent-minded dreamer with an unerring gift for making money who would later be diagnosed with Asperger syndrome, would prove to be the ultimate mark.

In 2009, on the advice of Montpelier, Sarao entered into a complicated dividend-stripping scheme that resulted in a major reduction in his tax bill, according to a close adviser to Sarao who spoke on the condition of anonymity. Happy with the result, Sarao went a step further the following year, the person said.

Among Dupont’s crew was Miles MacKinnon, a polished so-called introducer who had left school for a stint as a rugby player before heading to the City of London. For four months in 2010, MacKinnon became the only other director of Sarao’s firm.

Around the same time, Sarao set up two employee benefit trusts in the Caribbean island of Nevis, according to a document filed in Sarao’s case. He plowed his earnings into those trusts, then gave himself interest-free loans to trade with and live on, the adviser said. The arrangement meant Sarao all but avoided paying corporate taxes. One vehicle was named the “NAV Sarao Milking Markets Fund.”

Dupont and MacKinnon said in an e-mail that they “did not introduce or advise” on the Nevis trusts.

Sarao had an uncanny ability to attract controversial characters. He sought advice from tax specialist Andrew Thornhill, who in 2015 would be charged by the British barristers’ industry group with five counts of professional misconduct. And, as the Wall Street Journal reported, one of Sarao’s trusts was, for a period, affiliated with David Cosgrove, the Irish director of Belvedere Management who has been barred by Mauritius authorities from serving as a company officer because of regulatory violations. Thornhill declined to comment. Cosgrove didn’t respond to e-mails.

In 2011, the British government ended the benefit-trust gravy train. Sarao paid back the loans and restructured his business. Montpelier was investigated and dissolved, and about 3,000 of its customers were ordered by a judge to pay 200 million pounds in back taxes. Fraud charges against two directors were later dropped.

MacKinnon and Dupont—along with a third partner, Ryan Morgan—then founded MacKinnon Dupont Morgan, which was later reborn as MD Capital Partners. The firm describes itself on its website as a boutique private equity firm.

They leased an office in Mayfair, home of hedge funds, Michelin-starred restaurants and private members clubs. MacKinnon joined the Worshipful Company of International Bankers and the executive board of the Special Olympics. He and Dupont set up about a dozen companies between them, focusing on industries such as renewable energy.

Dupont and MacKinnon said in their e-mail to Bloomberg that they “never made, or introduced investments to projects that are purely driven by tax breaks” and that at the time they got involved in renewables there weren’t any tax incentives in place. Morgan, who left the firm, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

By 2011, Sarao had trebled his assets to 42.5 million pounds. He agreed to become an investor in an Isle of Man-based entity called Cranwood Holdings, set up to acquire land in Scotland that would one day house wind farms, according to two advisers to Sarao. Documents on the enterprise filed in the British dependency are light on detail, but the advisers say Sarao put about 12 million pounds in Cranwood—money they say Dupont and MacKinnon could access.

Dupont and MacKinnon said in their e-mail that Sarao conducted “substantial independent due diligence” before investing in Cranwood and that he approved all of its payments. One of their companies, Wind Energy Scotland, is funded by and provides project management services to Cranwood.

The pair also acted as agents for more exotic ventures, such as sending divers to search shipwrecks for sunken treasure. The returns on offer were never less than impressive. Sarao, who told acquaintances he harbored aspirations of becoming a billionaire, invested in several. All were tame compared with what came next.

Sometime in 2012, Sarao was introduced—again through Dupont and MacKinnon—to a squat, intense Mexican named Jesus Alejandro Garcia Alvarez, who was looking for investors for his company IXE Group. Garcia said he was the scion of a family of billionaire landowners and industrial-scale farmers with swaths of land around the world. He had arrived in Zurich from Latin America a few years earlier and had been working hard to build a reputation ever since.

IXE was conceived as a one-stop shop for high-net-worth individuals, offering services ranging from asset management to event planning to advice on private schools. Then, around the time Sarao met Garcia, the company’s website underwent a radical overhaul. Gone were the concierge services. IXE was henceforth a “conglomerate of companies worldwide” involved in “agribusiness, wealth management, commodity trading and venture capital.”

Articles appeared in the Swiss media profiling the mysterious young man making waves among Zurich’s business elite, including pictures of Garcia wearing a poncho over his suit, arm outstretched across Bolivian salt plains he said he owned. One newspaper put him on its annual rich list. Garcia was invited on Bloomberg TV to talk about his family’s quinoa interests, then on CNBC to discuss the “white gold rush” for lithium.

Garcia had all the trappings of a successful entrepreneur: half a dozen sports cars, a small but well-appointed office in the center of Zurich, a glamorous Russian wife. He even joined the Swiss board of the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights, an organization whose U.S. directors include Tim Cook and Martin Sheen.

Garcia flew to London and met with Sarao two or three times, according to people with knowledge of the matter. In an interview on IXE’s website, Garcia laid out his pitch to investors: “We are offering alternative investment vehicles that provide constant returns to investors. The investment in real economy makes the advantages obvious—investors are benefiting from constant returns generated from actual transactions with zero speculation and zero volatility.”

Garcia told Sarao he would get an annual 11 percent return, the people said, and assured Sarao that any money he handed over would be used only as collateral, not put at risk. He also introduced Sarao to Swiss banking contacts, they said. The trader was again restructuring his business, this time around an Anguilla-based vehicle called International Guarantee Corporation.

Sarao did some due diligence about IXE, according to one adviser, but he seems to have overlooked a few red flags: The company website is littered with spelling mistakes, and several executives are members of Garcia’s family.

Garcia initially agreed to meet to discuss this story, then opted to respond to questions through a colleague at IXE. The colleague, Dominic Forcucci, wrote in an e-mail that Garcia hadn’t done anything improper and that IXE “properly disclosed the risks of investments” to Sarao. A lawyer representing Garcia, William Wachtel, later said that Garcia described any allegations against him as “baseless and without merit.”

On Aug. 20, 2012, documents show, Sarao agreed to give about $17 million to Garcia and his company—by far his biggest investment and a substantial chunk of his net worth. He later invested an additional $15 million, according to a person with knowledge of the matter. Even though they’d met on only a handful of occasions, he would describe Garcia to associates as a friend.

Sarao may have been particularly trusting, but he wasn’t alone in buying into the IXE miracle. Former employees interviewed by Bloomberg describe Garcia as charming and, on first meeting, impressive. He offered commissions to third-party agents to send prospective investors his way, ensuring a steady stream of business and creating a buzz around the firm.

In 2014, Garcia signed a deal to acquire Banca Arner, a Swiss lender in decline after allegations that it had helped former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi hide money. To coincide with the transaction, Arner’s new marketing chief, Garcia’s wife Ekaterina, issued a press release announcing it had appointed a new chairman: Michael Baer, a great grandson of the founder of private bank Julius Baer Group and a respected figure in Swiss banking.

IXE just needed sign-off by Switzerland’s financial regulator, Finma. In order to seal the deal, Finma told Garcia he’d have to come up with 20 million Swiss francs ($18.7 million) in capital and account for where it came from. After heated meetings with the regulator and the owners of Arner, Garcia offered to hand over the money in unmarked gold, according to two people with knowledge of the talks. Without a stamp, the gold was unacceptable to the regulator, and in the end Garcia walked away from the deal, leaving Baer and a raft of other new recruits frustrated and embarrassed, the people said. Baer and a spokesman for Finma declined to comment.

For the time being, though, Sarao had no cause for concern. IXE sent him periodic statements showing the interest accruing in his accounts. As ever, he was happy to let it sit there and grow.

By then, Sarao’s readiness to consider almost any opportunity that offered an attractive rate of return was well-established. After another strong year in 2013, Dupont and MacKinnon introduced him to Damien O’Brien, a physically imposing Irish entrepreneur with aspirations to revolutionize the online-gaming industry.

The unique selling point of O’Brien’s company, Iconic Worldwide Gaming, according to a pitch document seen by Bloomberg, was that it allowed gamblers to bet on movements in currencies and securities using an interface that looked like an online casino, with a roulette wheel and buttons for “higher” and “lower” instead of red and black. The patented software was called MINDGames, short for Market Influenced Number Determination games.

The concept may not have pleased Gamblers Anonymous, but the financial projections were enticing. O’Brien predicted in the pitch document that Iconic would go from a standing start to a cash balance of 110 million pounds by the end of its third year. There were also some reassuring names on the board: Robin Jacob, a U.K. appeals court judge, and David Michels, a former deputy chairman of Marks & Spencer.

In July 2014, documents show, Sarao invested 2.2 million pounds in Iconic. Cranwood Holdings extended loans of an additional 1 million pounds, according to one Sarao adviser. He was, several times over, the largest investor in the company.

Dupont and MacKinnon said in their e-mail that Sarao was an experienced gambler and trader who conducted his own due diligence on the gaming sector before investing. They also said they objected when Sarao told them he planned to lend money to Iconic. O’Brien didn’t respond to requests for comment. Jacob and Michels said they were no longer board members.

In the months following Sarao’s investment, O’Brien went on a campaign to increase Iconic’s profile. The company sponsored World Touring Car Championship driver Rob Huff and filmed a slick advertisement with mixed martial arts superstar Conor McGregor. O’Brien and his employees were photographed ringside or wining and dining clients. In one shot taken in Las Vegas and posted on Twitter, a line of promo girls posed in matching uniforms with Iconic logos emblazoned on their hot pants. In another, O’Brien stood next to a matte-black Rolls-Royce with the license plate DAMI3N.

By the time Sarao was arrested in April 2015, he had about $50 million tied up in investments around the world, according to people with knowledge of the matter who even now aren’t positive it’s all accounted for. It was only as his lawyers tried to recoup the money that he was forced to face up to the possibility that it was gone. Sarao was released that August after his parents put up the family home as collateral against the bail of 50,000 pounds.

In November of last year, following an unsuccessful extradition fight, Sarao flew to Chicago where he pleaded guilty to one count of wire fraud and one of spoofing, which entails placing bids or offers with the intention of canceling them before they’re executed. He was ordered to pay $38.4 million to the CFTC and the Justice Department, which determined that, of the money he made by day trading, only $12.8 million came from cheating the market.

Sarao is scheduled to find out the length of any custodial sentence later this year. In the meantime, he has been allowed to return to Hounslow, where he is banned from trading and, despite pushing 40, placed under the care of his father.

Sarao’s lawyers are no closer to getting their hands on the money beyond about 5 million pounds seized from his trading accounts after his arrest. The CFTC and the Justice Department have joined them in the hunt, according to people close to the situation. The agencies could try to compel banks holding Sarao’s assets to give them up, but that might not be easy because most of the money is outside the U.S. Spokesmen for the CFTC and the Justice Department declined to comment, as did Burlingame, a former Justice Department prosecutor who represents U.K. targets in U.S. investigations.

IXE told Sarao it would return the cash in instalments in 2015 and 2016, according to a person familiar with the matter. The deadlines came and went, but no money has been produced. Garcia is rarely seen driving his sports cars around Zurich anymore, according to former associates. In October, German magazine Brand Eins skewered what it portrayed as his outlandish claims about plots of land in Bolivia and Mexico and linked Garcia to Burton Greenberg, who’s serving eight years in a Florida prison for fraud.

Former IXE employees interviewed by Bloomberg say that Garcia spent whatever he brought in to fund his own lavish lifestyle and that projections he gave in presentations to Sarao, Baer and others were plucked out of thin air. Still, Garcia’s efforts to acquire a bank continue. In August, IXE announced it was buying Private Investment Bank in the Bahamas from Swiss firm Banque Cramer & Cie. The deal is scheduled to be completed this month.

Garcia hasn’t been accused of any wrongdoing. Forcucci, the IXE spokesman, said the company is “working to return the money in a fair and equitable manner to its investors.”

Iconic went into liquidation in January 2016. A company hired to advise it on resale options said O’Brien had underestimated the cost of breaking into the online gaming market by about 10 million pounds.

Sarao’s lawyers have been unable to retrieve his investments in Cranwood despite repeated requests, owing to its convoluted offshore ownership structure, according to a person with knowledge of the situation. Dupont and MacKinnon said in their e-mail that Wind Energy Scotland has been working to get funds to Cranwood.

From their base in Berkeley Square, the pair last year started another company focused on renewable energy, Celtic Asset Management, which offers “access to a substantially higher return profile, with less capital at risk.”

Meanwhile, Sarao is back in his bedroom. The computer that got him into so much trouble is gathering dust in a Washington evidence room. Depending on how much the authorities are able to recoup, he will probably spend the rest of his life paying back the money he owes. If they really want it, they could always lift the trading ban, one associate quips: He’d make it back in no time.

Monday, 1 January 2001

It's Official

To clarify what I mean when I say 'official' results, since there is unfortunately no recognised source for closing prices (or starting prices to use the horse racing term) for any sport with which this blog concerns itself.

Sharp And Soft Books

From Nikolai Livori - Sportsbook Soft or Sharp

The sports betting industry is fragmented into Sharp and Soft books, and of course a mix in between. But what does this mean? We use a more precise term by referring to them as Asian and European books respectively - with Asian books being sharper than European ones.

Soft bookmakers like the renowned Unibet, Betsson, William Hill etc. make use of a lot of traders within the company that use manual or semi-automatic odds movements to ultimately rely on gut feelings, knowledge and game statistics within the industry. They operate with high margins. They do not welcome sports traders and most of the time limit such customer accounts thus falling into the trap called a “false positive”. What if the person you just limited could have been one of your VIP Casino players? Soft bookmakers like these target mostly punters and gamblers and usually have other products to support their sports book such as Casinos, Poker, Bingo etc.

The Sharp bookmaker model is based mostly on mathematical and highly efficient automatic risk management tools. They do employ traders as well to compile odds, however balancing their book is sharper and done with the help of mathematical models. Most of the time they are able to offer better prices in the industry, due to being faster and sharper than Soft bookmakers. Most of them also do not limit bettors and accept large bet stakes, thus they welcome traders and punters alike. Examples of such books are Pinnacle Sports, ED3688, SBOBet etc. Their profit is derived on smaller margins due to a huge turnover.

Being a Soft bookmaker is becoming very challenging nowadays, considering that the Asian market is expanding at a very quick rate. Why would I place a bet on a Soft book for a much cheaper return (and also risk being erratically limited) when I could place a much larger bet at a much better price through an Asian book?

Bundeslayga System

In September 2010, I noticed that the strategy of laying certain Home Favourites in the German Bundesliga was consistently profitable, making this an ideal system for mitigating Betfair's Premium Charges.

The system has been profitable in both the Bundesliga and Bundesliga.2 leagues.

Initially the system was to lay (oppose) most teams priced at odds-on but as more data has become available, the exact range has expanded.

Because this is a Laying System, it’s really only suitable to be applied on the Betting Exchanges, although you could combine backs of the Draw and away team if you were desperate.

A note on the prices used. Since I don’t have reliable historical Lay prices, I use closing price data from Pinnacle Sports, courtesy of Football-Data.co.uk, and remove the margin using the "Equal Margin" method detailed in Joseph Buchdahl's excellent book "Squares & Sharps, Suckers & Sharks".

This resulting 'fair' price is usually very close to the closing Exchange price, but remember there’s commission to pay on Exchange winning bets. In the seasons since 2012-13 for which we have the new system has lost money only once in both Bundesliga.1 (2013-14) and Bundesliga.2 (2016-17), and overall only in that one (2016-17) season.

Here’s a real life example as I write this, from Pinnacle Sports:

The Lay price, calculated by removing the margin is 1.673, very close to Betfair’s 1.68.

UMPO System

UMPO is an acronym for Underdogs MLB Play-Off and is a simple strategy which backs odds-against underdogs in the Major League Baseball Play-offs.

Since 2004 - the first year for which I have data - it has been a steady winning strategy, and the following returns from a US site can generally be beaten on the exchanges.

Maria's Laying System

Maria's Laying System achieved some notoriety in 2005-2006 when its creator (Maria Santonix) increased a starting bank of £3,000 to six figures (£100,603.78 to be precise) in 303 days.

What came to light only later was that Maria’s father was connected with several bookmakers, and through her contacts, she was able to obtain privileged information that helped with her selections. No doubt this contributed considerably to her winnings.

While most of us do not have access to the kind of data Maria had, we can still profit from her laying system. But we must state that her selections were, in fact, remarkable. Of her 4,131 selections over 303 days she achieved 3,547 wins; in other words, a strike rate of almost 86%. While Maria’s system does not in any way help us with our selections, it does provide a mathematical plan that will help us maximise our winnings.

This way of staking is actually truly excellent but it wont change a losing system into a winning one. This is something that many people need to understand before they try and replicate what Maria did. Maria felt she had a winning system for laying horses and so she used this staking plan to compound the profits and grow her bank. Something she certainly achieved by turning £3000 into £100,000 within a year!

I've been reluctant to start off this thread, because I'm frightened of its turning out to be the kiss of death. You have what you imagine to be a good system and start to explain it in public, and suddenly a wheel comes off?

I've come up with a laying system.

I'll record its daily selections and results in this thread, until I get jeered off, anyway.

I'll try to post each day's selections by 1.00pm at the very latest, but I don't think I'll often manage to post them the night before.

Comments, general heckling and questions (but not about the details of my selection-process, please) are very welcome as we go along, but I'd better start off with something like an "FAQ".

STAKING: I want to minimise risks and maximise returns, of course (who doesn't?), which are always pretty difficult, not to say conflicting, objectives to combine. Like all forms of betting, the selections are only a part of the story. Betting on horses is notorious for people being able to have good selections and still lose money through poor money management. With laying in particular, IMHO the commonest reasons for failure are under-funding (not having a bank big enough for what you're trying to do) and disillusionment (getting too easily fed up with an inevitable losing run).

This isn't the time or place to get involved in a big discussion about whether the selections or the money management are more important - it suffices to say that without both aspects being good, sensible, reliable and proven, it's not possible to make steady profits.

The two common staking methods for laying are:-

(i) Laying to a fixed stake: I don't use this for two main reasons: first, the "accidents" are proportionally too expensive; secondly, it seems to me that it fails adequately to make the profits "deserved" after successfully identifying and laying shorter-priced losers.

(ii) Laying to a fixed liability: I don't use this either, because it's inherently mathematically unsound - it ignores the fact that accidents are far more likely to happen at the lower end of the scale: if I lay a 2/1 favourite (i.e. I lay it at an exchange price of 3.0), the overall risk of that bet losing (the horse winning) is of course higher than one which was a lay at 8.0 (7/1).

Instead I try to combine the best of both worlds by using what looks like a complicated mixture of the two systems mentioned above, but it's actually perfectly straightforward.

My staking system: I lay in three distinct exchange-price-bands of fixed backer's stakes.

At one end of the scale, if the exchange price available about the horse is less than 3.5 (less than 5/2), I lay to a stake of 1% of my current laying system bank. At the other end, if the price is between 7.5 and 11 (the latter figure being my cut-off: I don't lay anything higher than 10/1), I lay to a stake of 0.4% of my current bank. If the price is in-between these two bands (i.e. prices of 3.6 to 7.4), then I lay to a stake of 0.6% of my bank. As they say in those TV infomercials, "But wait - there's more!": I also combine this staking plan with a ratchet system (see below).

The are two other advantages with this staking system: first, the practicality of the situation when using the exchanges is that the backer's stake (rather than one's own liability) is the value which has to be typed into the little box on the screen, and this makes it quick and simple to do; secondly, nearly a year's figures have proven to me that this method minimises the variability of the results, and that's very, very important.

To summarise, with examples based on a starting bank of £3,000 (if you're reckless enough to try them, you can scale up or down proportionally to your own bank).

Prices below 3.5: lay to 1% of bank - backer's stake £30 (my liability under £75)

Prices from 3.6 to 7.4: lay to 0.6% of bank - backer's stake £18 (my liability £46.80 - £115.20)

Prices from 7.5 to 11: lay to 0.4% of bank - backer's stake £12 (my liability £78 - £132)

Ratchet System

If making profits, I increase all stakes in proportion to the bank on a daily basis. (I'd love to do it on a bet-by-bet basis, but that would assume that anyone following the system can be glued to their screen all afternoon, which isn't realistic. If you're working for a living - shock horror: please excuse my language! - you need to be able to put the bets on during your lunch-hour.)

This means that at the end of each day, the next day's "current bank" figure is known. For example, if there's a good start and the £3,000 bank grows, then the stakes are worked out as proportion of the new higher figure, and increase slightly the next day. This may sound insignificant but it makes a huge difference to the results.

In contrast, after a losing day, I don't reduce stakes unless and until 35% of the highest level of the bank is lost, when I essentially re-start using the same percentages, but now of the new "65%-sized bank".

Example: from a £3,000 start, if there's a net loss on the first day, the next day I still stake as if from a bank of £3,000 (i.e. to backer's stakes of £30, £18 and £12 depending on the price about each selection) until reaching £1,950 when those backer's stakes would become £19.50, £11.70 and £7.80 until the bank gets back up to £3,000 again (or - dare I mention it? - down to £1,267.50 - a further 35% loss).

The 35% drop is always worked out from the highest point of the bank. If it happens (and so far it hasn't - famous last words!) I'll explain it again.

It may sound a bit complicated but it's actually very simple. Not easy, but very simple.

Please don't imagine that I'm claiming this to be a perfect laying system. There are one or two anomalies in it, but after lots of analysis and calculation in the early days, over the last year I've found this system practicable, straightforward and robust. And that's what matters.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS / PRACTICALITIES ABOUT THIS SYSTEM AND ITS RESULTS

(i) It's essential to keep (at the very least on paper) a separate bank for this system: the money can, if unavoidable, be mixed up in an account with other betting funds, but at the very least the "books" must be kept separately, otherwise you don't know where you are - it's not possible to win in the long run without keeping good records -oooh, contentious!

(ii) Terminology: there's always understandable confusion about discussing laying. For the record, if there's any apparent ambiguity, I'm always referring to the bet rather than the horse. So if I say that out of the day's selections, three won and one lost, and that the day's strike-rate was 75%, I mean that three of the horses lost and one was a winner on which I paid out. (But if that's the actual strike-rate every day, we won't get far: mixed-price-bracket laying systems generally need a very high strike-rate).

(iii) This is a slow and steady system, not a get-rich-quick scheme, and any attempt to turn it into that, or to escalate the stakes when losing, is destined for disaster. With laying, in particular, the swings and arrows of outrageous fortune can be particularly vicious, and it's all too easy for gradually accumulated profits to be wiped out quickly by an uncharacteristically unlucky run. I hope that my staking system allows for this, to a large degree.

(iv) Some of the selections tend to shorten in price and others tend to drift. The reality is that it's not possible, overall, to lay at SP and I would therefore be misleading people about my profits if I quoted the results to SP. So I'm going to keep two separate sets of results.

1. SP + 10%: These results will quote all prices to SP + 10% (i.e. as if the price, from the layer's point of view, was 10% worse than SP).

2. My own actual results, recording the prices I've found and used.

No method of doing this is going to be perfect, but before deciding on this method of keeping the results, I've talked it over with the Administrator and we've decided, hopefully, that this "double results" system is the least open to criticism.

(v) If a selection is priced at more than 11 on the exchanges when I first look at it (and this really isn't going to happen often, because they make me nervous), then with one exception I leave my bet unmatched at 11 and just wait and see what happens. The exception is that if it's priced at more than 14 to lay, I cross it off the list completely and don't even go back to look at it again (this is a half-hearted attempt to avoid becoming the victim of any "major coups"). In the "starting-price + 10% results", I won't be recording as a bet anything that set off at more than 10/1.

(vi) The exchanges charge a variable commission on profits. I'm going to allow for the highest commission at the most expensive of the exchanges, and deduct 5% from all wins. (Note that this is calculated on a "per event" basis, so if you lay two or more horses in a race, the commission is charged only on your net profit on that race.)

(vii) This is (comparatively, at least) a "high turnover" system. The idea is that every bet made represents "value" and has a positive expectation, and therefore the more of them there are, the better the returns. It's not for the faint-hearted! Back these with real money at your own risk and never with money that you can't afford to lose.

(viii) I've found that it's nearly always a mistake to "pick and choose" with this system. Lay all the selections (that can be done within the cut-off of 11) or none of them.

(ix) When I put the bets on, I don't always just take the best current price, depending partly on how much of a hurry I'm in and whether I have shoe-shopping plans for the afternoon. Unless I think the price is particularly likely to lengthen (see "Lay, Back and Think of Winning" by Nigel Paul for the best simple explanation of how you can judge this), I'm likely to leave my lay unmatched at a price in-between what's available to back and what's available to back. Usually my lay will get matched. But I only do this if I can keep an eye on it, and change my mind quickly about what price to lay at if the market moves against me.

(x) Within my cut-off of 11, the market moving against me when I have an unmatched bet is not a reason for me to abandon a lay: if it's part of the system and it's not above 11, I lay it.

(xi) The overwhelming majority of the lays in this thread will be win lays, but there will be the occasional place lay included too. These are much rarer, but I have a very high strike-rate with them.

(xii) Patience and discipline lead to profits.

While she kept her selection process to herself,

What criteria do you use to select the lays?Ooooh, I could tell you, Atc ... but then I would have to kill you ...

The thing is that a lot more of my selections drift than shorten in the market. This is, really, how I get away with listing the selections here in the first place, to be honest, without it having much effect on the prices I lay to myself. I take loads of early laying prices if I think they'll drift, which I try to judge, with varying degrees of success by "trading-style chart-reading" on the exchange.The times that this causes me a problem are (like yesterday's accident) when it's too early to tell, for a late evening runner, because even Betfair doesn't have enough liquidity on those earlier in the day. So I just leave positions unmatched at 11.0 (just like I leave a lot of earlier ones unmatched at 7.4).I'm gradually been learning from nearly 2 years of doing this, now, that overall I make more profit and a better POI on my higher selections, and less on my lower ones. I happen to know a few full-time professional layers (mostly because my father's one of them!) and they all tell me the same thing: the way to make secure and steady income is by laying in the sort of 5.0 or 6.0 up to 15.0 bracket; nothing much shorter - with the exception of some "value shorties" which I'm stuck with for the moment anyway, because my system produces them and I'm usually pretty strict about including system selections and not just leaving them out because I "don't like the look of them" because my judgement isn't good enough to start doing that, and I'm putting it mildly!So for me, making the cut-off any shorter is an absolute no: I want to make it longer, really, not shorter. I imagine that the reality of available prices is such that if you make it 10.5 or less, you'll actually be missing out a much higher proportion of the selections than you might expect just from looking at the SP's, and really you'll end up following "selected selections" rather than "selections". It might be a good and viable and profitable system, and it might work well for you, and I'm not trying to talk you out of it at all; but it's not my system, and it's not what works for me.

It's incredibly hard work. I have, in my case, been particularly lucky to have had very good teaching (and from quite a young age!) from a very long-term successful punter who happened to be my father, an opportunity obviously not available to the overwhelming majority of punters. But it has also been very hard work, and very many years of it.

I think that a lot of people imagine that it's as easy as dreaming up a suitable system or method that works, and then just sticking to it. The reality is that that's terribly, terribly difficult to do, and things tend to have a limited shelf-life of viability and profitability anyway.

I think it's also very true that different styles and approaches suit different people.

What many people are looking for, in my opinion, is (one way or another) a "short-cut" and there really aren't any. Or at least, the ones that do very occasionally arise are pretty difficult to identify and also not so easy for many people to follow (like this thread, perhaps!). But the reality is that many people find that when they follow a successful system, it isn't successful for them, because actually following a successful system is something that some people are (for various different reasons) not so well equipped to do.

The point I'm trying to build my way up to making here is that developing, analysing, researching and using "systems" (for the benefit of those of us who are not exactly steeped in racing, barely know one end of a horse from the other and have no real, on-the-ground experience at all), isn't in any way a "quick or lazy substitute" for all

that knowledge and experience; it's every bit as time-consuming, difficult, specialised and labour-intensive as any other approach. It just entails a different sort of work.

When asked:

"is there a reasoning behind your price limits, i.e. up to 3.5, 3.6 to 7.4, 7.5 to 11?

she generously expanded on her thinking with a detailed reply:

Well, yes there was when I produced it a couple of years ago, after fiddling about with many different possibilities (and having some much more sophisticated software available then than I have now).I wanted to be able to break it up into four chunks (there's 11.5 to about 15.5 as well, but those don't appear in this thread) for all the reasons given in the thread's first couple of posts, to be able to avoid the worst features of laying either purely to fixed stakes or purely to fixed liabilities, and these turned out to be the most natural dividing lines, the first cut-off of 3.5 mostly for "money management reasons" and the second of 7.5 on "frequency" grounds (the point being that in practice, many selections that I want to lay tend to cross that line at some point during their market travels and it therefore seemed a potentially good discipline to create one's arbitrary chart/table landmark there, "waiting for 7.4" being an activity with a reasonable expectation of avoiding disappointment often enough to make it worthwhile).I haven't looked at it much since then, I'm suitably embarrassed to say, and of course there's absolutely no reason whatsoever to imagine that it would be suitable for anyone else's selections. This is why I'm always (even now) a bit taken aback when people thank me for the "brilliant staking system" which they are adopting for use with their own selections. I would actually think it far more promising if they were adapting it for use with their own selections (after studying a few thousand results in detail with appropriate spreadsheets etc. - not by "guessing"!!), rather than just adopting it! But this, I think, is really what you're asking about, and my answer is "yes; do that".

I think the overall concept of having these different price-brackets as a way of breaking the thing up, rather than using the "sliding-scale approach" of fixed liability is a valid and sound one, and constitutes a staking system which is safe and profitable if the selections are profitable at fixed liability to start with, obviously.

There will always be people who will try to come up with a staking system which will make profitable a system that wasn't profitable to start with at level stakes/liability; and even more alarmingly there will always be some who apparently manage to do it (the key word, of course, being "apparently"!), but there have to be large numbers of "new layers" coming into the markets all the time and eventually wiping themselves out: that's how markets work, I'm afraid.

The key sentence there is that the system is profitable because the selections are profitable at fixed liability, not because there is anything magical about the laying bands.

Elo Ratings In Football

Often incorrectly written as ELO, Elo ratings actually

take their name from the inventor, Arpad Elo, a Hungarian-born American physics

professor and Chess player who invented the ratings method as a way of

comparing the skill levels of players from his game. Its use has expanded, and

has been adapted for several sports including American Football and basketball,

but also in football, and it is their use here that is the focus for the rest

of this article.

The

Basics

The essence of Elo ratings is that each team has a

rating. When comparing two teams, the team with the higher rating is considered

to be stronger. The ratings are constantly changing, and are calculated based

upon the results of matches. The winner of a match between two teams typically

gains a certain number of points in their rating while the losing team loses

the same amount. The number of points in the total pool thus remains the same.

The number of points won or lost in a contest depends on the difference in the ratings

of the teams, so a team will gain more points by beating a higher-rated team

than by beating a lower-rated team.

Raw Elo

suggests that both teams ‘risk' a certain percentage of their rating in each

contest, with the winner gaining the total pot, i.e. their rating increases by

the losing team’s ante. In the event of a draw, the pot is shared equally.

A Simple

Example

A simple example shows how this works when two evenly

matched teams meet, and both have 5% of their rating at risk. Arsenal and

Chelsea both have a rating of 1000 so both teams risk 5%, i.e. 50 points, and

the pot contains 100 points.

There are

three possible outcomes.

1) Arsenal

win, and the result of this is that Chelsea’s rating drops by 50 to 950, and

Arsenal’s rating increases by 50 to 1050.

2) Chelsea

win, and the result of this is that Arsenal’s rating drops by 50 to 950, and

Chelsea’s rating increases by 50 to 1050.

3) The result

is a draw. The pot is divided between the two teams, resulting in the ratings

for both Arsenal and Chelsea remaining unchanged at 1000.

A Second

Example

A second example shows how this works when the home side

is stronger. Manchester City (with a rating of 1200) plays Aston Villa (with a

rating of 1000). Again, both sides risk 5% (60 points and 50 points respectively),

so the pot contains 110 points.

The three

possible results and their effect of the ratings are:

1) Manchester

City win, and the result of this is that Aston Villa’s rating drops by 50 to

950, while Manchester City’s rating increases by 50 to 1250.

2) Aston Villa

win, in which case Manchester City lose their 60 points and their rating drops

to 1140, while Aston Villa gain the 60 to improve their rating to 1060.

3) The result

is a draw. The (60+50) 110 points in the pot are divided by two, resulting in

Manchester City’s rating dropping by 5 points to 1195, and Aston Villa’s rating

improving to 1005.

A Third

Example

A third example shows how this works when the away side

is stronger. Wigan Athletic (with a rating of 800) plays Manchester United

(with a rating of 1000). Again, both sides risk 5% (40 points and 50 points

respectively), so the pot contains 90 points.

The three

possible results and their effect of the ratings are:

1) Wigan win.

Their rating increases by 50 to 850, while Manchester United’s rating decreases

by 50 to 950.

2) Manchester

United win, in which case Wigan lose their 40 points and their rating drops to

760, while Manchester United gain the 40 to improve their rating to 1040.

3) The result

is a draw. The (40+50) 90points in the pot are divided by two, resulting in

Manchester United’s rating dropping by 5 points to 995, and Wigan’s rating

improving to 805.

The table

below summarises these combinations of pre-match ratings, match results, and

updated ratings:

Some

Issues

All very simple, but for football, it is much too

simple. Anyone with a basic understanding of football can see a number of

problems with the above examples. One obvious problem is that home advantage is

not taken into account, so in a match between two evenly rated teams, in the

event of a draw, the away side should be rewarded, and the home side penalised.

In the ‘teams evenly rated’ example above, a draw for Chelsea at Arsenal is

clearly a better result for them than it is for Arsenal, and it is illogical

that both teams walk away at full-time with the same rating as when the match started.

In Part Two, I will look at some ways in which these problems can

be remediated.

In Part One we explained the basic premise of Elo ratings, and illustrated how they are applied. Part two will offer some suggestions on how the principles of Elo can be enhanced to make our ratings more useful. It is important to understand that these are only suggestions. There are no hard and fast rules that dictate what these parameters should be. There is no right and no wrong, only what works and what doesn’t work.

We finished

Part One with an example of two evenly rated teams, risking the same percentage

of their ratings, and identified one major problem which is that an away draw

is better than a home draw, and it is thus illogical for both teams to end the

match with the same rating as they started.

The

Punter’s Revenge: Adjusting For Home Field Advantage

One way to handle this is by having the home team risk a

slightly higher percentage of their rating than the away team. Back in the

early 1980s, two authors, Tony Drapkin and Richard Forsyth wrote a book called “The

Punter’s Revenge: Computers In The World Of Gambling”, which was targeted at

computer literate punters at a time when the personal computer was just

becoming popular. One of the more memorable chapters was on rating football

teams, and the author’s suggestion, after running trials, was to use 7% for the

home team, and 5% for the away team. I’ve found no reason to diverge too far

from these numbers.

If we re-visit the earlier examples from part one, using the 7% and 5% numbers, the results become:

When the teams

are identically rated going in, after a drawn match, the away team gains

slightly, the home team loses slightly, something that intuitively seems right.

If you’re not happy with the adjustments that 7% and 5% give you, then there’s

absolutely no reason not to tweak these, but I would caution against exceeding

10% or going below 3%. Changes in rating should be in modest increments, but at

the same time, not too modest that it takes a season for a declining team’s

rating to reflect its form.

Result

Adjustment: Incorporating Margin Of Victory

Now to address the next problem – match results. Basic

Elo doesn’t quantify wins. A win is a win, whether it is by one goal or by a

dozen. Most readers will agree that this is an unsatisfactory state of affairs,

and will make adjustments. One method is to increase the percentages that each

team risks, but to award a certain percentage of the pool to the winners /

losers varying depending on the margin of victory / defeat.

For example,

Arsenal and Liverpool are both rated at 1000, and Arsenal are at home. The pot

(or pool) contains 120 points, 70 from Arsenal, 50 from Liverpool. If the game

finishes 6-0 to Arsenal, it’s reasonable to give all the points to them. My own

preference is for a four-goal win or more to be sufficient to secure the entire

pot. A three-goal win is pretty good, and earns most of the pool, whereas a two-goal

win earns a little less, and a one-goal win the minimum. The following table is

a suggestion.

Winning is

worth at least 70% of the pot, with the margin of victory becoming less

significant as it grows. Winning 6-0 rather than 5-0 is neither here nor there,

but winning 1-0 rather than drawing 0-0 is much more significant – even though

the difference between both pairs of scores is just one goal. You may want to

consider a 1-2 defeat as a better result than a 0-1 defeat, but again,

decisions such as these come down to personal preference. With all the time in

the world, you might analyse goal times, and conclude that a 2-0 win decided in

the 30th minute is a stronger win than a 2-0 win in which the second goal was

scored on a breakaway in the 93rd minute with the vanquished team pressing hard

for an equalizer. A fair conclusion in my opinion, and an example of how you

can modify Elo to suit your own needs, and add flexibility based on the amount

of time you have available.

Maintaining

accurate ratings is time consuming, and in previous years I would attempt to

maintain ratings for the Premier League, Football League and Conference as well

as the Scottish Leagues. These days, I restrict my tracking to the top

divisions of England, France, Germany, Italy and Spain, in part because there

is a wealth of data readily available to input, and on the output side, there

are many liquid markets available. It is also my opinion that in the lower

leagues, ratings are not so stable. A modest amount of money goes a long way,

as recently seen with Crawley Town and Fleetwood Town, and ratings can soon be

out of date.

In Part Three, I will look

at more ideas for maintaining accurate ratings.

In Part Two, I looked at one way in which Elo ratings could be improved by measuring the strength of a win based on winning margin. However, the low scoring nature of football means that the match result often does not reflect the performance of the teams.

We have all

seen games where one team has dominated, only to lose 0-1 to a goal very much

against the run of play. If you limit your input to this single figure, goals

scored minus goals conceded, you risk entering less than accurate data into

your ratings.

While it is

true that Birmingham City did beat Chelsea 1-0 on November 20th, 2010 is it

fair and reasonable to award 100% or 70% of the points available to them? You

might think it is, and I would say that is your decision to make, but my take

on it is to look behind the result and use some of the other data that is

readily available these days.

When deciding

what data I should include, my rule is that there is a correlation between the

data and goals. For example, simple logic tells you that there is a

relationship between shots, shots on target, and goals. 10 shots, of which 5

were on target, doesn’t necessarily mean that a team will score 2 goals, but

for each league there are fairly consistent ratios which we can use.

Charles

Reep: Incorporating Shots On Goal

Pioneering football statistician Charles Reep began his

research in 1950 (at 3:50pm on 18 March while watching Swindon Town play

Bristol Rovers to be precise) and discovered (among other things) "that

over a number of seasons it appears that it takes 10 shots to get 1 goal (on average)".

This average

will of course vary from season to season, by league and by team, but the

important thing is that there is a correlation between shots, shots on target,

and goals scored. A note here that some of this data has an element of

subjectivity about it, and you will often see major differences in the

statistics for the same game from individual observers.

Again, how

much effort you want to put into this is a personal choice. Researching the

leagues you are interested in will show there are differences, which you can

incorporate if you wish, for example as of 2011, the EPL is more efficient at

converting shots to goals than Serie A.

I would

however caution against changing these parameters too frequently once you have

determined reasonable values, with my preference being to use an average for

the past three seasons. The soccerbythenumbers.com website often has some

interesting articles on this subject, along the lines of this entry from

January 2011:

Adding

Meaning

This data is important because it allows you to enter

more meaningful data into your calculations. Arsenal 2 Chelsea 1 is a start,

but in my view, the data is made more valuable by entering the shots and

shots-on-target figures also, so you now have for example Arsenal 2:5:12

Chelsea 1:8:19 - a set of numbers that might reasonably lead you to conclude

that Chelsea were a little unlucky in that their goals scored were lower than

might have been expected.

You can

include other data too, although I have yet to see any evidence of correlation

between free-kicks or yellow cards. Red cards can obviously be more

significant, but you would want to factor in the amount of time remaining at

the time of the dismissal. A headline of "10 man City see of United"

might sound dramatic and sell newspapers, or draw clicks, but if the dismissal

was in the 90th minute, it's a little misleading to say the least.

In Part Four,

I'll look at corner kicks and whether this additional data should be included

in your Elo based ratings.

Dangerous

Corner

I concluded Part Three with a discussion about what data can or should be

included when adjusting a team's Elo ratings. It might seem logical and

reasonable to include corner kicks, but perhaps surprisingly, the evidence

shows that there is essentially no correlation between the number of corner

kicks and goals scored. The English Premier League is actually the strongest,

while Serie A and La Liga are the weakest.

This isn’t to say

that corners do not lead to goals. One of the problems is that the readily

available data is based on match totals, i.e. they do not reveal how many

corners lead to a goal; only that over the course of a match, Team A had 2

goals and 12 corners. Both goals may have come from corners, but at this

'macro' level, there is no evidence that says there should be say one goal for

every eight corners.

Having decided what data to include, we are no win a

position to expand upon the simple table seen in Part Two, which looked like this:

Putting

It All Together

By using more data than simply the round figure of

goals, it is possible to 'more accurately' reflect the result of a game. I

mentioned in Part Three the real-life example of Birmingham City beating

Chelsea 1-0 on November 20th, 2011, and we will use this match as an example of

how additional data can be incorporated.

Birmingham

City had one shot, and they scored one goal. Chelsea had 24 shots, 9 were on